Do Jardim, um Oceano: Panmela Castro, curated by Igor Simões

Panmela Castro: from the garden, an ocean.

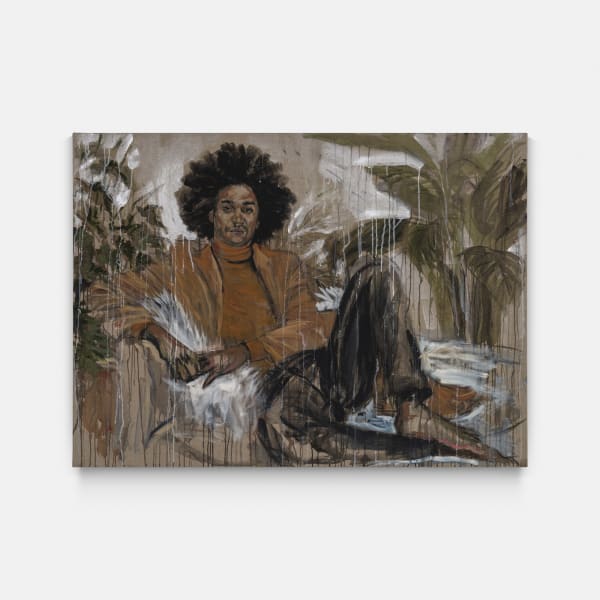

Arriving at the foyer of Galeria Francisco Fino, in Lisbon, we immediately see a self-portrait of Rio de Janeiro-born artist Panmela Castro in which some of the main elements of her work are apparent: the trickling that results from quick brushstrokes that attempt to capture the instant (a tradition of modern impressionist painting); the ability to capture the air surrounding the portrayed person; the plants, the lighting, the atmosphere of a garden – in and of itself a type of space carrying a series of historical layers that also include 18th century European artistic tradition, with its conflicted vision of nature either as controllable by human action or as the place of in-submission. But this is not just any garden. The brushes, the palette, everything reminds us that this garden is the artist’s place of process and creation. In her self-portrait, Panmela is at once relaxed and absorbed. Her eyes are on the pages of a book. But not any book! In her hands is a copy of Gayatri Spivak’s seminal work, whose title consists of a rhetorical question which has oriented most thinkers who are keen on founding a different way of understanding the world: Can the subaltern speak?

There is another clue that can guide us across the exhibition. The garden does not occupy a neutral place. Neutrality does not exist. Therefore, it is impossible to disregard the fact that the series of paintings featured at the gallery were made in a garden in Lisbon, in a Portuguese garden. The fact that the artist is holding Spivak’s book in Portugal changes everything: What is at stake when black Brazilian artist Panmela Castro crosses the Atlantic and decides to encounter black, white, Afro-Asian, cisgender, trans, non-binary, Portuguese, African, migrant people in Portugal? That is precisely the moment when an ocean starts to appear among the architectures of the garden.

*

We all know that the Portuguese colonial enterprise translated into the removal of people from their homelands and their forcible displacement to other crown-controlled territories; African lands were taken from their original owners and turned into places of dominion, extraction of wealth and labour to serve the Portuguese empire. The ocean was the road used by Portugal to submit a whole part of the world. But we should also remember that any attempt at submission must deal with the in-submissive, with that which does not bend.

Gradually, the Atlantic Ocean also became a space that no longer submitted to the notion of national borders established by Europeans who saw themselves as the discoverers of that which had always been there. A series of traditions was created both above and below the water. And that was how a world of practices, languages and cultures was woven in murmurs, exchanges, survival strategies. In the course of this flow Panmela Castro’s country, Brazil, gradually ceased to be the main Portuguese colony to become the main destination of black men and women, who endured the largest forced displacement process ever witnessed by humankind: the African diaspora.

Unavoidably, these detoured lives did not merely occupy the territory under domination. They also countered the dominators, threatening their supremacy at the very core of their ancient cities, streets, houses, gardens. Portugal and the city of Lisbon saw the appearance of people that evaded their European models and, along with them, came voices and knowledges that were relegated to a place of subalternity. However, the subalterns who arrived (and keep arriving) can speak. And not only can they speak. They create and recreate artistic languages, modes of existing, ways of redrawing life.

*

Panmela Castro operates the transformation of the garden into an ocean. By deploying her processes of affective drift, she gathers a choir of voices and existences that result from the world invented by the Atlantic’s salty water. As they arrive at the garden, the people she now encounters, and with whom she creates, bring in the oceanic part of their stories. They bring with them displacements made by the story of their bodies and the bodies of those who came before them. Their lives are the concrete proof that subalternity was but an attempt.

Her encounters, which can last for different lengths of times, are the material for her portraits. These paintings bring the opposite of a notion of immobility. Of someone who ‘poses’ for another who represents them. While canonically the portrait is seen as the instant in which someone is paralysed and becomes the subject to be captured by the painter, this notion does not apply to the poetic operation that turns a garden into an ocean.

The paintings featured here are the record of a performance carried out to activate encounters. Each represented person was also the creative agent of their own image. These portraits are not the single, exclusive narrative of the painter about the bodies that submit to her. Nor are they the absolute truths of the portrayed. The outcome is the result of an act of full trust in the power of being together; of being with; of launching a proposition and use it to let randomness in. Panmela is a performer. A performer who is also a great painter. An artist with a sophisticated artistic ability and repertoire.

During one of our talks, the artist showed me another dimension of her process, which somehow had escaped me. She told me that the people in the paintings are also part of a network. A vast network of affects that starts with encounters and expands into the dimensions of everyday life. She told me stories shared with some of the people that appear in the portraits on show. She also told me how each of those lives connected to others that came to her encounters and how for her that process takes us to another act: the exhibition itself and its celebrations: An opening morning, afternoon or evening when those people, as they see the multitude of voices rising amid the conversations, the dribbling brushstrokes and the affects, in fact look beyond the portraits towards the enormous network they express. And at that moment, those who were the subalterns celebrate and remember that, resorting to the power of what we do together, it is possible to turn a garden in Lisbon into the Atlantic itself. To turn a garden into an infinite ocean.

Igor Simões, Curator

-

Panmela CastroPode o subalterno falar, 2024Oil on linen170 x 200 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroPode o subalterno falar, 2024Oil on linen170 x 200 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroDennis Correia, 2024Oil on linen110 x 150 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroDennis Correia, 2024Oil on linen110 x 150 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroYen Sung, 2024Oil on linen170 x 110 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroYen Sung, 2024Oil on linen170 x 110 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroAnastácia Costa e Deolinda Cardoso Costa, 2024Oil on linen170 x 110 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroAnastácia Costa e Deolinda Cardoso Costa, 2024Oil on linen170 x 110 x 8 cm -

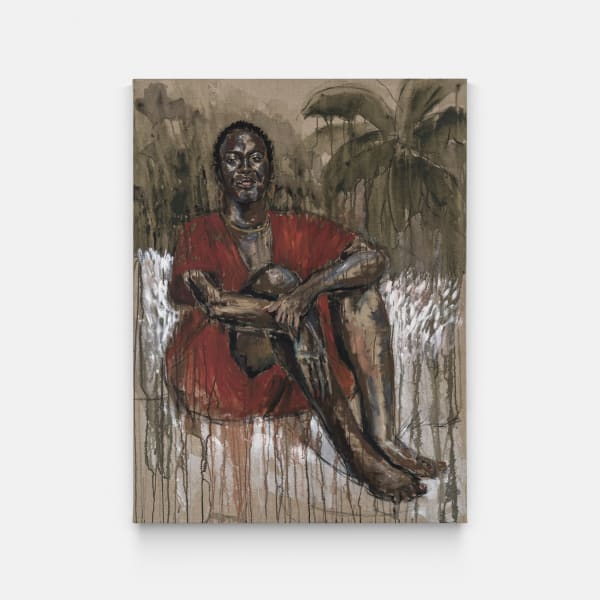

Panmela CastroAlexandre Santos (Xando), 2024Oil on linen170 x 110 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroAlexandre Santos (Xando), 2024Oil on linen170 x 110 x 8 cm -

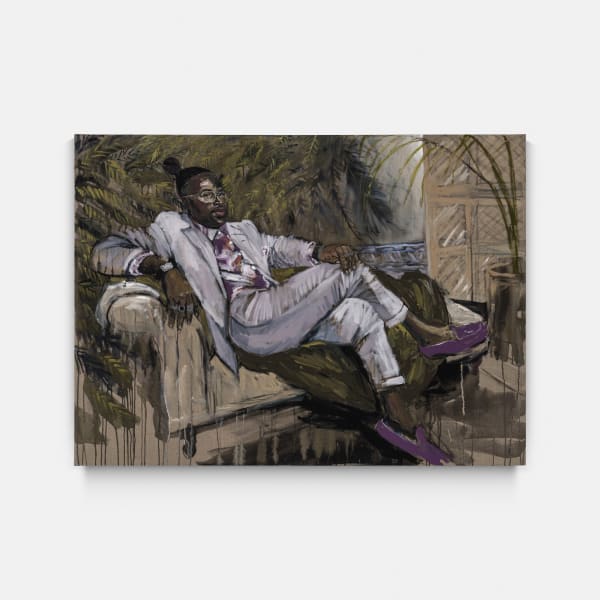

Panmela CastroTelmo Galeano (Tekilla), 2024Oil on linen110 x 150 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroTelmo Galeano (Tekilla), 2024Oil on linen110 x 150 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroKemberling Martinez, 2024Oil on linen120 x 90 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroKemberling Martinez, 2024Oil on linen120 x 90 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroPati Nakamura, 2024Oil on canvas90 x 120 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroPati Nakamura, 2024Oil on canvas90 x 120 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroAmina Bawa, 2024Oil on linen120 x 90 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroAmina Bawa, 2024Oil on linen120 x 90 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroNamalimba Coelho, 2024Oil on linen150 x 110 x 8

Panmela CastroNamalimba Coelho, 2024Oil on linen150 x 110 x 8 -

Panmela CastroOseias Baltazar, 2024Oil on linen90 x 120 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroOseias Baltazar, 2024Oil on linen90 x 120 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroAnastácia Costa, 2024Oil on linen110 x 170 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroAnastácia Costa, 2024Oil on linen110 x 170 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroFelicia Hunter, 2024Oil on linen90 x 170 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroFelicia Hunter, 2024Oil on linen90 x 170 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroAuto-retrato com Francisco Fino, 2024Oil on linen170 x 200 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroAuto-retrato com Francisco Fino, 2024Oil on linen170 x 200 x 8 cm -

Panmela CastroJuca da Cruz, 2024Oil on linen110 x 170 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroJuca da Cruz, 2024Oil on linen110 x 170 x 8 cm -

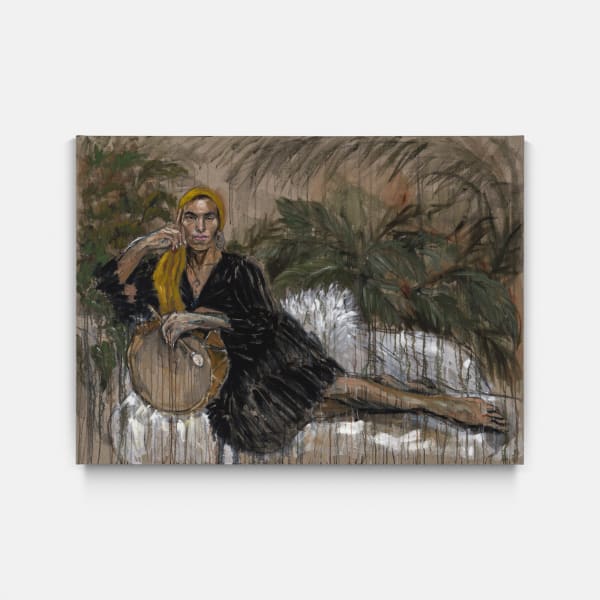

Panmela CastroLola Bahjan, 2024Oil on linen110 x 150 x 8 cm

Panmela CastroLola Bahjan, 2024Oil on linen110 x 150 x 8 cm